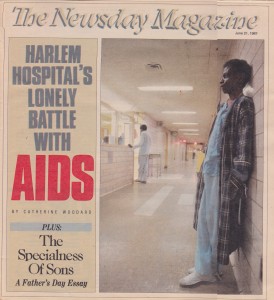

A Harlem Hospital’s Lonely Battle With AIDS

THE SLENDER WOMAN in striped pajamas circled by the entrance to the nurses’ station for the fifth time in 15 minutes. She had just been admitted to the hospital for meningitis and possibly AIDS, and she was looking for a doctor who could give her methadone.

“I shouldn’t have to put up with this,” she told Christine Velarmino, the senior nurse on the floor. “I haven’t been medicated all day.”

Velarmino, working her second consecutive eighthour shift, was interviewing a new admission for whom she had not yet found a bed – a tall, thin tubercular man who was cursing her and the hospital.

It was Memorial Day weekend and the middle of the 4-to-midnight shift on the 12th floor of Harlem Hospital Center. About a third of the patients on the floor had AIDS or tuberculosis. Coughs pierced the sticky summer air. The smell of diarrhea mingled with disinfectant. Mice nibbled at red bags of infectious waste that hadn’t been picked up for hours. Two nurses hadn’t shown up. The pharmacy still hadn’t sent up half the medication orders. And now this guy was screaming for slippers, pajamas and a bed. “Oh lordy,” he moaned. “You mean to tell me there are only two nurses for each side?”

Dr. Cheryl Holder ignored his complaints and grabbed a blue paper mask from a nearby isolation cart. “Sir, you should be wearing a mask. You don’t have to put it on very tight, but you could infect other people.”

He reluctantly tied it behind his head. But as soon as the doctor and nurse turned their backs, he flipped it up on his forehead. “I can’t breathe with this,” he told the woman hunting for methadone. She pressed her forehead to the window of the nurses’ station and waited. It was not her first trip to the ward. The nurses used to chase her out after visiting hours when she came to visit her boyfriend, who has AIDS.

These two patients – young, black, poor and drug abusers – are at great risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome. They signal what could be the worst public-health crisis of the century, and they come to a place already hard-pressed to cope with them. Health officials estimate that at least half of New York City’s 200,000 addicts carry the AIDS virus. Most live in the city’s poorest neighborhoods and infect each other with shared needles, infect their lovers through sex and infect their children in the womb. When they can no longer survive on the streets, they end up in public hospitals such as Harlem.

The hospital, like the patients, is vulnerable to the AIDS epidemic. In a person, the AIDS virus destroys the immune system and the patient dies from other infections. In an understaffed, underfunded public hospital such as Harlem, the epidemic threatens to drain the resources and morale of an institution already overwhelmed by the needs of the poor.

AIDS patients – who are often very sick and need a great deal of care – are flooding the public hospitals in an era when cost containment has become a medical cliche and the shortage of nurses is a national emergency.

“I am overwhelmed,” Charles Windsor, Harlem Hospital’s executive director, said. “I don’t think we are nearly as panicked as we ought to be.” Harlem Hospital Center, in a commercial area at Lenox Avenue and 135th Street, has never been a particularly easy place to work. It opened in 1887 in a three-story Victorian building on the East River as an emergency branch of Bellevue Hospital with a mission that has never changed – to provide medical care for the poor. Public hospitals typically aren’t the kinds of places that advertising agencies would choose as the backdrops for commercials. Harlem is no exception.

The welcome to the hospital quite often is a broken elevator in the lobby of the Martin Luther King Pavilion, an 18-story blue-and-white brick building. There simply isn’t the money, time or staff to go much beyond medical immediacies. In a hospital with a larger maintenance crew, all the clocks probably would be set on the same time.

The medical care itself came under attack last summer, as did a $31-million contract with Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons to hire and supervise Harlem’s doctors. A controversial state study identified Harlem as one of 19 hospitals where people died because of deficiencies in treatment. The City Health and Hospitals Corp., which runs the 11 municipal hospitals, questioned the methodology of the study.

Now the hospital faces AIDS. State officials estimate statewide hospital expenses for AIDS will top $1 billion in 1991. Harlem Hospital is already feeling the strain. The number of AIDS patients has doubled in the past year and may double again in the next. AIDS patients require 40 percent more nursing time than more typical patients and run up twice the bills for drugs. The hospital now issues a daily update of medicines that are unavailable or in short supply.

Once patients are no longer eligible for federal or state reimbursement, the hospital gets stuck with the bill. Often, Harlem Hospital also gets stuck with the patients.

On many days, about 60 AIDS patients fill nearly a quarter of the hospital’s general medical and pediatric beds. Bellevue typically has more AIDS patients, but Harlem has the more difficult population to care for – and to discharge. The patients are more often children and very frequently homeless. On the pediatrics ward, toddlers who have never left the hospital are taking their first steps in walkers tethered to cribs. Adults, who also have been abandoned by their families, languish in hospital beds for months while they wait for housing. One woman has been stuck in the hospital for more than a year.

“People know that their favorite dress designer may have AIDS,” said Dr. Margaret C. Heagarty, Harlem Hospital’s director of pediatrics. “And there has been considerable whoop-de-do about heterosexual transmission because the people in Larchmont are concerned that the virus is going to get there. But they have leapt right over the kids I’ve got here.”

New York has been the home of about a third of the AIDS cases in the nation, and health officials predict there will be 40,000 cases and 30,000 deaths in the city by the end of 1991. More than half the AIDS victims are homosexuals. That percentage is decreasing, however, as large numbers of drug abusers are afflicted. AIDS is not transmitted by casual contact, but shared hypodermic needles are perfect conduits for infected blood.

City Health Commissioner Stephen C. Joseph said the disease is now likely to spread fastest in poor communities. “That’s the thing that we fear most in terms of the future of the epidemic,” he said. “It is the minority groups who are particularly vulnerable.”

Drug abuse has made AIDS yet another risk of poverty, yet another risk for minorities. Blacks and Hispanics make up 20 percent of the nation’s population but 39 percent of its AIDS victims.

The discriminatory overtones of AIDS are painfully apparent to Heagarty each time she walks down her ward and sees the children who are dying. Eighty percent of the 183 cases of pediatric AIDS reported in New York are related to intravenous drug use in one or both parents. Ninety percent of the children are black or Hispanic. All the babies at Harlem Hospital fall into those categories.

They die, sometimes quite quickly, because their immature immune systems are weak matches for the virus. A 3-month-old child admitted through the emergency room in recent months died of pneumonia about a week later. While the child struggled under a miniature oxygen tent in intensive care, her doctor polled other experts in Miami and Newark just in case they had stumbled across a new treatment. But she could offer little hope to the mother, who came to her in tears, blaming herself for the disease that was killing her child.

On the same ward, a 3-year-old boy with stiffened limbs cried when the attending physician lifted his head. There was a feeding tube in his nose and an intravenous line in his arm. Last summer, he was riding a tricycle and talking with his parents. A 1-yearold in intensive care was so small that a finger-size Band-Aid stretched around her leg twice. This six-pound child had been battling pneumonia and chronic diarrhea since birth. A small pink rabbit decorated the oxygen tent. The only sounds were the beeps of a heart monitor.

But not all the babies testing positive for the AIDS antibody need to be in the hospital. One 11-month-old has never been sick, and the doctors are optimistic she may never develop the disease. She is stuck in the hospital because she has no home. Wearing a bright pink dress with a white apron, she slept peacefully in a room of six cribs. Her older brother, who has been diagnosed as having AIDS, pulled himself up in the adjoining crib. Several times he has fought back from near death, but for the last five months the 2-year-old has been stable. He is a sturdy-looking tot with a little round belly. He has just learned that a clown will pop out when he pushes the button on his toy. There are bald spots on the back of his head because he has spent so much of his life in a crib.

He and his sister were abandoned at birth by a mother whose pull to the world of drugs overpowered her ties to her children. Their only visitors are volunteers. They are among six children on the ward who could leave if there were somewhere for them to go. Because of the stigma of AIDS, Harlem Hospital has been able to place only one child in foster care.

The children live in a world of institutional limitations, where white baby shoes sit on electronic monitors, where the diaper bin is marked with an “infectious-waste” sticker. The cribs look like cages, tall boxes with aluminum bars and plastic safety hoods. Walkers sometimes are anchored to door knobs. Televisions and radios provide stimulation when people can’t.

“It’s very sad because this is such an abnormal environment,” Dr. Elaine Abrams said. A child she had just returned to a crib reached between the bars for the doctor’s red stethoscope. “Children should not be learning to walk in a hospital.”

Nurses and doctors pause to play with toddlers, but they must move on to the next patient, the next diaper, the next crib. A donated pink carpet did not meet hospital rules so there is no place for the babies to crawl, no place for them to explore their world without barriers.

Hale House, a residence for the infants of drug-addicted women, recently announced that it plans to open a home for 15 AIDS babies from Harlem Hospital. But the nonprofit group has just begun to raise the home’s $750,000 annual operating budget.

Harlem may have a waiting list for the home even before it opens, particularly if city health officials follow federal recommendations that all high-risk pregnant women be tested for AIDS. If the percentage of babies testing positive is at all similar to infection rates for military recruits from the neighborhood, Harlem Hospital is easily delivering more than 100 babies a year with the virus. Medical authorities say some patients who test positive for the AIDS antibody may go years without developing symptoms of the disease. In some cases, they believe, mothers may pass only the antibody and not the virus to their children. Social workers have had no better luck placing healthy homeless infants who test positive in foster care than those with symptoms of the disease.

“Now they are going to have to invent beds or I am going to have to build mangers, aren’t I?” Heagarty said.

She is a sturdy, plain-spoken woman whose father was a doctor in rural West Virginia. Now 52, she came to Harlem nine years ago from New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, looking for new challenges. “Suddenly, I find myself in the middle of a bloody epidemic which in some ways is the most serious health problem this country has faced in 50 years.” She sees few signs that government is responding to the crisis.

“The city hospitals and other city hospitals around the country have got a group of children desperately ill from some very deprived backgrounds. We as a society have a duty to care about them. It is a moral issue. We don’t allow children to die without trying to do something, no matter what color or what social class. That is such a simpleminded truth and I think often it gets lost.”

At the entrance to the pediatric ward, there is a brightly colored mural of the neighborhood with Manhattan landmarks in the background. But faces are the focus of the wall, faces of several colors – men, women and children. At the center of this community, there is a mother holding a child.

The AIDS children on the ward are symbolic, too. They are a warning of how this virus that is actually difficult to catch threatens to devastate a disadvantaged community. Drug addiction has always been a flirtation with suicide – death by overdose, violence or disease. It has always brought pain to friends and relatives. But AIDS has redefined their risk. Now it can mean death. Social workers at Harlem Hospital know entire families dying from AIDS.

“It’s a much bigger problem than people seem to recognize yet,” said Windsor, the hospital’s administrator. “It’s like people have their heads in the sand.”

If compassion fails to budge the people with the purse strings, fear might. Health experts are convinced that intravenous drug users could be the catalyst for the most rapid heterosexual spread of the disease. Of the 225 New York women who have contracted AIDS through sexual relations, 189 were the partners of drug abusers. Only 23 were the partners of bisexual men. People who are callously unconcerned about gays and addicts are likely to care about their own sexual freedom. Many white Americans weren’t very concerned about drugs, either – until pushers started growing up on their own middleclass playgrounds. AIDS, like drugs, won’t be confined to the ghetto.

“The ones that should be worrying is these ones that is walking around here with their white collars, white shirts, making $75,000 a year, the ones that are supposed to be straight,” a Harlem AIDS patient said. “They had better be worried. That piece they go sneak out on their wife on Saturday night. They don’t know where she’s been and how many people she’s been with.

“It’s the domino theory,” he said. “Push one domino and all of them are going down.”

But there are other arguments on why more resources should be channeled into minority communities to combat AIDS, particularly for prevention and for development of alternativecare facilities. One is strictly economic. Thirty-seven pediatric AIDS patients at Harlem Hospital have run up bills totaling $3.3 million since 1981. It costs hundreds of dollars a day of public money to maintain an indigent patient with AIDS or AIDS Related Complex, ARC, in an acute-care hospital.

During Memorial Day weekend, the late tour on the 12th floor unfolded like a long, slow dream that returns night after night with the same plot and similar characters. A tall, skinny man with bandaged ankles hobbled down the corridor dragging a rack of intravenous fluids beside him. He looked like a stork with a wounded wing. He stopped at the window of each room to beg for a cigarette. The man has tuberculosis, and doctors suspect that he may develop AIDS.

The yellow isolation carts outside almost every door on the 12th floor are symbols of the growing numbers of AIDS and tuberculosis patients. The rise in TB is one reason why hospital officials suspect that the numbers of AIDS cases has been underreported. Junkies – whose immune systems are already weakened by years of drug abuse – often die of debilitating diseases such as TB long before AIDS can be diagnosed. Haiti is now the only place in the world with a higher incidence of TB than Central Harlem.

“Harlem wasn’t what it is now,” Velarmino said as she remembered her introduction to the hospital four years ago. She is a petite woman and her hair was pulled back with barettes and anchored in a small, braided pigtail. Like many members of the staff, she was recruited at a foreign job fair. She came to Harlem because it was the only place that offered to pay the airfare from her native Philippines.

Thirteen nurses usually worked during the day then. Now there are at least three but never more than six. The nursing shortage isn’t a result of the AIDS epidemic. But it has made it more difficult to endure.

Each time Velarmino looked up from a chart or the medication cart or hung up the phone, a patient hovered nearby. Those who were well enough to walk didn’t bother to ring the nurses’ bell because they knew that the staff was likely to be busy. So they took their requests directly to the hallways. A woman in pink pajamas complained that someone had stolen her coat. A woman who wanted Tylenol knocked on the door of the men’s bathroom when she couldn’t find the doctor in the library or the nurses’ station.

“Every time you come to work, there are not enough nurses,” Velarmino said as she hung a replacement bag of intravenous fluid beside a Hispanic man with AIDS. He has been in the hospital since September, battling AIDS, meningitis, herpes and TB. He slept fitfully, slumped so far down in the bed that the feeding tube in his nose seemed to be connected to a legless body.

The bright pink sticker at the foot of his bed warns the staff to avoid direct contact with blood and body fluids. Routine precautions are nothing extraordinary for a staff that regularly treats hepatitis and syphilis.

But there is a difference with AIDS. There is no known cure.

“Of course you are afraid,” Dr. Gamal Hanna, a second-year resident from Cairo, said as he peeled off surgical gloves. “In this hospital, potentially everyone has AIDS.”

Last month, the federal Centers for Disease Control outlined three cases where health-care workers contracted the virus from skin contact with the blood of AIDS patients. Just a few days earlier, Hanna had rushed to the Hispanic AIDS patient to reconnect an intravenous line. “I fixed it with my bare hands. It was a reflex action.”

He is fairly certain that none of the man’s blood touched an abrasion on his hand. But there is concern that comes from continuous contact. And often there are not even enough gloves.

“There is almost no way you can avoid excessive exposure,” said Dr. Cheryl Holder, who is considering taking the antibody test herself. “The AIDS patients are so sick that you end up taking blood cultures all the time. And you see so many of them.”

ACTUALLY, many of the problems presented by AIDS aren’t very different from the difficulties the hospital has faced all along. Harlem Hospital has dealt with large numbers of chronically ill drug abusers and abandoned children for many years. But it seemed less pressing when the patients could be discharged one-by-one into city shelters, when the children didn’t die during their long waits for foster care. With AIDS, these patients are backing up on the wards.

Douglas Roberts, 34, was living in an abandoned Cadillac when he came to the emergency room a few days before Christmas. He was hospitalized with pneumonia, and he was told he has AIDS. His confidence in the hospital was shaken when a resident changed his diagnosis to AIDS Related Complex, ARC, a less severe stage of the disease. Patients with ARC can be discharged to a city shelter. The mistake was caught by a senior physician, and Roberts was placed back on a waiting list for housing. But the incident underscored the frustration of residents tired of treating large numbers of AIDS patients.

As he spoke about the incident, there was a weariness about Roberts that seemed deeper than his sickness. His father kicked him out of the house when he was 15 after he pawned his mother’s engagement ring. He dropped out of high school in the 11th grade. He spent a couple of years in jail for burglaries. He injected cocaine for about three years.

“Most of my troubles I brought on myself,” he said in a darkened room, illuminated by the glow of a television soap opera. “I was always looking for a shortcut. The older I get, I begun to realize there was no shortcut in life, not nary a one. The only shortcut in life is death.”

Taped above his bed was a newspaper editorial about hospital negligence, a color picture of Christ and a clipping from a South Carolina newspaper about a friend’s mother and her prize-winning tomatoes. He came to a few conclusions, propped under this triptych during recent months.

“I’m going to get out of this nuthouse, even if I ain’t got a place,” he said, stroking a few long hairs at the end of his chin. “Whatever life I have left, I don’t want to spend it laying in here. This is just like being in jail.”

For a patient such as Roberts, hospital life is more than unpleasant. It could be medically threatening. The Health and Hospitals Corp. has made it a policy not to discharge AIDS patients without housing – theorizing that a person with a depressed immune system shouldn’t be sent to a shelter full of people carrying infectious diseases. A hospital can carry some of the same risks. Some officials concede that they worry about lawsuits from hospital-acquired infections.

When an AIDS patient doesn’t need to be in the hospital, it’s bad for the patient, bad for the hospital and bad for the taxpayer. The bill is at least $600 a day.

By comparison, $70 a day buys a private room, a view of the Hudson and orchids in the dining room at Bailey House, the city’s only residence for people with AIDS. Six former Harlem Hospital patients are among the 33 men who live at the Christopher Street residence in Greenwich Village, run by the not-for-profit AIDS Resource Center. The fees are paid through supplemental Social Security.

“We could have filled Bailey House just from Harlem Hospital,” said Elinor Polansky, a social worker at the residence. “I had the impression that Harlem Hospital was being inundated.”

Finding alternative care for homeless AIDS patients is one of the topics each week when an interdisciplinary team meets to coordinate the hospital’s response to AIDS. People who would normally see each other passing in the hallways – physicians, nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, public health aides, discharge planners – meet for two hours each Thursday afternoon. They talk about what they can offer patients in the absence of a cure.

One of the answers has been an outpatient clinic for AIDS. Two afternoons a week, doctors from the infectious-disease division treat at least two dozen people with AIDS. In a hospital where most admissions come through the emergency room, it is rare for patients to see the same doctors and nurses week after week. At the clinic, even some of the patients greet each other by name.

“How are you doing?” a patient on the experimental drug AZT asked as he slid into one of the plastic molded chairs bolted to the floor of the waiting room. “Hanging in there, man,” a man in a purple seat answered.

Most waited quietly, staring blankly ahead. A few slept, slumped in their chairs. One man rolled up his pants and dabbed Vaseline on a skin rash. A young mother, who was sweating profusely, waited anxiously with her daughter. The child had parked a Big Wheel tricycle near the reception desk.

ONE 25-year-old Hispanic man waits for his brother at the clinic twice a month. They live in Brooklyn, but his older brother ended up in intensive care at Harlem because there were no beds at Bellevue when they went to the emergency room in October. He has noticed that there seem to be fewer empty chairs each visit and that more women are coming to the clinic. Sometimes, when the brothers leave, they visit clinic patients who have returned to the hospital. “It’s like you see some of them just slipping away,” the man whispered.

His brother is a favorite among the clinic staff, a 29-yearold artist who seldom has the energy to paint anymore. At the staff’s suggestion, he brought some of the paintings to the clinic this spring. Most were images of death, mummies masturbating, mummies praying, abstract mummies leaning on coffins. He started painting mummies before he knew he had AIDS. Some of the patients told him they understood that premonition.

Like most of the patients, he is on welfare, but unlike many, he has a family he can depend on for help. Still, he is thankful that the hospital arranged for a nurse to come to his apartment to administer the experimental drug he is taking to slow the damage of an eye infection. Other patients expressed similar gratitude. All of Harlem’s patients at Bailey House commute by choice from the West Village to the clinic for their medical care. AIDS has required a new perspective for the infectious-disease doctors who choose their field of specialization with a predilection toward cures. They came to hospitals such as Harlem to be firefighters for a whole host of diseases that are uncommon in white, middle-class communities. “You could make a precise diagnosis. You could grow it in a test tube and find a cure,” said Dr. Jay Dobkin, 40, chief of infectious diseases and the AIDS team. “Now we end up talking about quality of life.”

At the end of each Thursday afternoon meeting, the psychiatrist on the team encourages members of the group to talk about their own reactions to AIDS. Some have been reluctant to join in this informal group therapy. But almost no one reports being unaffected by the epidemic.

“It’s tough to watch people your own age die,” Dobkin said.

For Dobkin and others on the team, there is a sense of frustration that the biggest battles are beyond the hospital. They worry that the sense of urgency motivating them has not yet carried over into the community. There have been few politicians to champion the cause, no AIDS publicity walks in Central Harlem, no support network to match the Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

The reasons are varied. Those most at risk are some of the poorest, least-educated members of the community, whose families often are already overwhelmed with other problems. Many minorities still think of AIDS as a downtown disease cause of the early media focus on the spread among gays. Harlem’s political and religious leaders have found AIDS to be a troublesome topic that conjures up stereotypes about addicts and minorities and requires them to talk in explicit language about sex and drugs.

Two years ago, state health officials wanted to send outreach workers into the streets to warn addicts about AIDS and to encourage those who would not seek treatment for addiction to sterilize their needles and to practice safer sex. The program was quashed when city officials would not sanction it.

Now those efforts are begin ning in earnest. Both the city and state have assigned AIDS educators to Harlem. One group is concentrating initially on about 10 square blocks west of Fifth Avenue and north of 110th Street, an area with an estimated 20,000 drug abusers and a high incidence of AIDS-related deaths.

“Education is the only thing that is going to keep us afloat here,” said Jolene Connor, an associate director of the team. “There are just too many folk out there who don’t realize it’s their problem.”

Dr. James Curtis, director of psychiatry, has applied for a $350,000 grant to offer antibody testing and counseling to the 1,500 patients in the hospital’s methadone clinics. He also is lobbying for $1 million to bring the program into the hospital and neighborhood clinics in the hope of reaching 5,000 patients a year. The counseling would stress the importance of safer sex and the risk of sharing needles. PREVENTION is the only effective intervention we can offer now,” Curtis said. “It is extremely inappropriate that we are spending all our money on treatment.”

Inside a hospital-run methadone clinic about 20 blocks away, pamphlets on AIDS are tacked to the bulletin board. But a young woman sitting in a parked car outside the clinic said her counselor has never broached the subject, and she’s been too afraid to bring it up. She said she stopped shooting up five years ago. She tested positive for the AIDS antibody in September.

She cried softly as she talked about her fears. She no longer picks up her 10-year-old daughter for weekends because she mistakenly believes she might spread the virus with a hug or a kiss. She doesn’t understand why she feels so tired or why the glands in her neck often are swollen. She can’t persuade her boyfriend to take the antibody test. He blames her for not realizing that the years she shared needles with friends left her at risk.

She is 25. “How could I have known?” she said. “There is still a lot of ignorancy about it. That’s the biggest disease that is going on now.”

Christopher Sutherland, a 54- year-old cardiac patient on the 12th floor of Harlem Hospital, would agree. “The warnings should be emblazoned on the walls of Harlem as big as this hospital,” he said. “They do that with cigarette ads. Why can’t they do the same with this epidemic?”

While a light rain dampened Memorial Day plans across the city, Sutherland talked about the impact of AIDS on his hospital stay. He had demanded to be moved from a room with two AIDS patients – not because he was afraid of casual contact but because one of the AIDS patients always left a trail of urine on the floor on the way to the bathroom. Often, there was no one to clean up the mess for hours.

“Who is going to look after all these people?” he asked as he removed a cigarette from behind his ear. He sat on the corner of a crooked table, just across from the nurses’ station. It was half past midnight. Two nurses had left and two still waited for replacements.